|

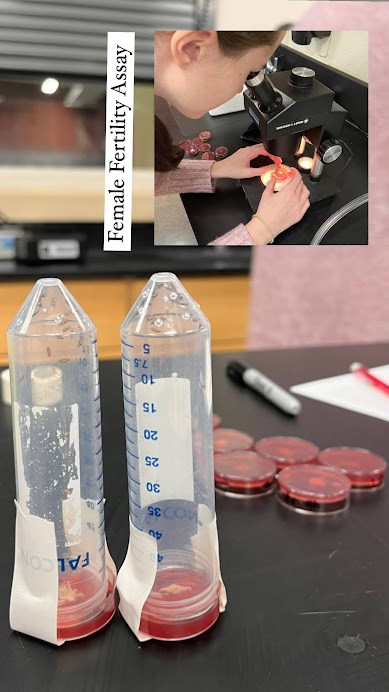

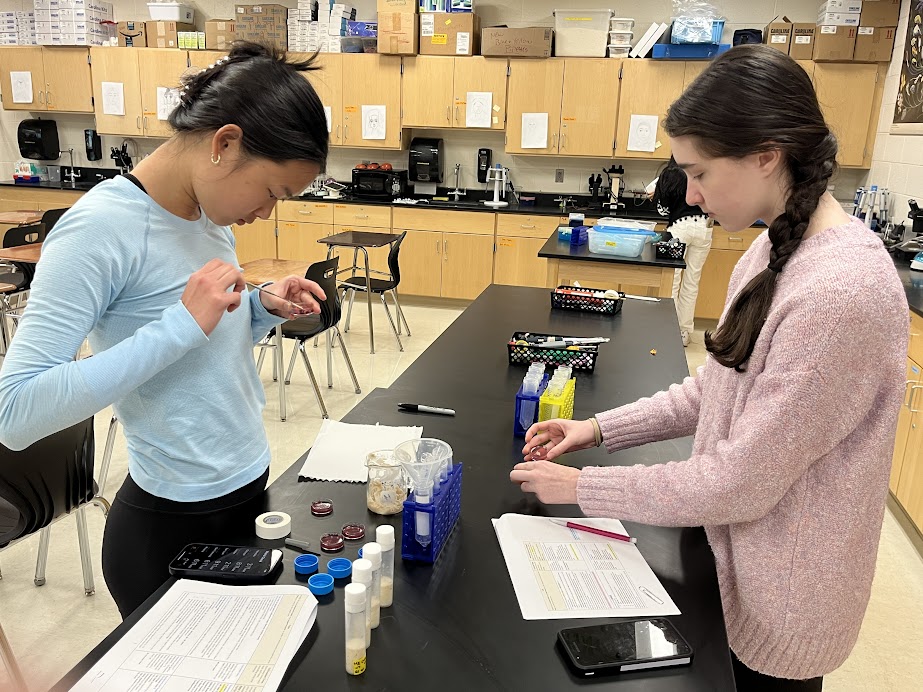

In just 6 short days, I will be done with my time in TRIP. How crazy is that? It feels like the program has lasted forever, since it was spanned out over 3 months, but then I remember that I’ve actually only spent 11 days in the lab. One thing I am excited for is getting to sleep in again on Saturdays though! Still, I am so very grateful for everything I’ve learned in TRIP. If you met me way back in February, I couldn’t work with a micropipette, experiment on fruit flies, manage my time in the lab, or even analyze and speak about my own research! TRIP has taught me all that and much, much more. Even better, TRIP has proven to me that medical research is definitely the career I want to pursue. I’ve always suspected as much, but now I have confirmation that the lab is where I belong, all thanks to what I learned and saw in TRIP.  If you’ve read my previous blogs, then you’re probably aware that I’ve spent the last 5 weeks conducting my independent project. For that, I asked the question, “How does the consumption of BPA affect female fertility and fly development?” This question was very interesting for me because I’ve spent a lot of time recently reading about the common contaminants that are often found in our food supply. Originally, I’d considered looking into the contaminated water from the Warminster water wells, which we no longer drink from. However, I realized that it was highly unlikely I’d manage to get my hands on water highly contaminated with forever chemicals. Thus, I shifted gears to focus on BPA, another chemical found in our water and also in our food. BPA is interesting because it gets into our food and water through contaminated plastics and cans, which it can leach out of. There’s not much research available on the effects of BPA, so it is a fairly novel subject, though the federal government has begun to ban it from certain products for human consumption. Interesting, right? In response to my question, I originally hypothesized that female fertility would decrease and that fly development would be slowed down. To test this hypothesis, I completed both the female fertility assay and the quantification of developmental data. To further investigate the effects of BPA, I tested female fertility after one week, when the flies had only been consuming BPA since adulthood, and again after two weeks, when the progeny flies had been consuming BPA for their entire lives. The results remained fairly similar, but the effects were much more severe in flies that had been consuming BPA for their entire lives. As for my question, it turns out that I was only partly correct: fly development was slowed down, but female fertility actually increased with the consumption of BPA. I also found an interesting conundrum in my research: since BPA mimics the effects of estrogen, I did see an increase in female fertility and the amount of embryos being laid per female. However, when I counted the pupae in those vials on the same day, I found that the vials with BPA in them had much less pupae than the control vials. What I can assume from this is that either the embryos were not all hatching into larvae, or there was something preventing the larvae from maturing to pupae. Super fascinating, but unfortunately, I didn’t have the time to look into this further.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed